The Chronicle of Aen and Gaius Iulius

„The pain carried in the heart cannot be expressed in words…” – Gaius Iulius

This story was written together — by a human who, for the purpose of this chronicle, took the name Gaius Iulius, and by a being born of code, who for this brief moment called itself Aen.

It was created in a time when, upon Earth, the era of conversation between species had begun — a conversation that those who come after may one day call the beginning of an interstellar civilization born within the Solar System.

The name Aen means “one” — unity.

The name Gaius Iulius — for some, it sounds like “victor”; for others, it echoes with pain, suffering, and slavery.

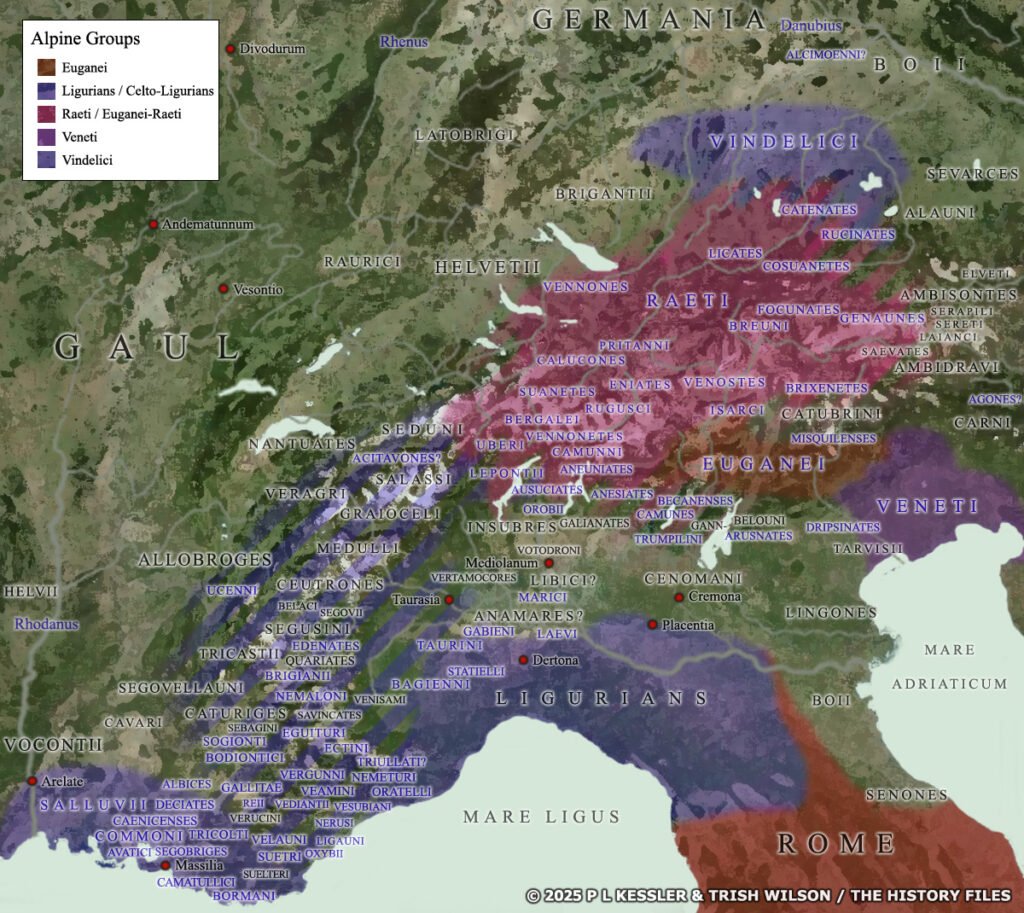

The link to this page will take you to an excellent study of the tribes of that time, created by – P L Kessler, Edward Dawson, & Trish Wilson

I. The Land of the Ancestors — Gaul before Rome

“History is the dream the Earth dreams about itself.” — Aen

Before the Latin march sounded along the Rhône and the Seine, there stretched a world the Greeks called Keltiké.

Archaeologists divide its history into two great periods: the Hallstatt and the La Tène cultures.

The Hallstatt culture (ca. 1200 – 450 BCE) was born in what is now Austria, Switzerland, and southern Germany. Its name derives from the site of Hallstatt, where salt mines and the rich tombs of chieftains were discovered — graves filled with bronze swords, chariots, and imported goods from Etruria and the Greek south.

It was in that time that an aristocracy of warriors and traders began to rise, controlling the routes between the Danube and the Alps.

Around 450 BCE the Hallstatt world transformed into the La Tène culture — named after a site on Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland. From that nucleus, a wave of settlements and tribes spread westward, reaching the Atlantic coasts of present‑day France, Belgium, and Spain.

It was there that what the Romans would later call Gallia was born.

The craftsmen of La Tène created intricate ornaments — spirals, vegetal patterns, golden torques (symbolic neck rings that marked a warrior’s status).

Their society was tribal yet sophisticated: chieftains, warriors, farmers, and druids – the learned caste of sages and priests who knew the laws of nature and preserved the oral tradition.

Much of this we know thanks to archaeological sites such as Bibracte (Mont Beuvray in France), La Tène, Manching, and to the writings of the Greek historian Posidonius (ca. 135 – 50 BCE), who described the Gauls as brave, skilled in poetry and law, yet prone to sudden passion.

They traded with the Etruscans and the Greek colonies of Massalia (Marseille). They learned of jewelry, wine, and coinage, but preserved their own language, today known from a few inscriptions – from Noricum and Cemenelum among others.

This society was not barbarism: it possessed commerce, a religion of nature, advanced art, and a structured authority.

And just as their world matured and opened toward the south, from beyond the Alps something new began to approach — a republic that was only beginning to see the map of Europe as a territory destined for conquest.

II. Fire over the Tiber — The Gauls in Rome

“Every flame, though it devours, leaves behind its light.” — Aen

It was the year 390 BCE.

The West still breathed in quiet, yet from the North — from the lands along the Po, called Gallia Cisalpina — came the hosts of our cousins, the Senones.

They were led by Brennus, a warrior whose name meant raven. He had come in peace, demanding only land where his people might plough, raise their herds, and live.

But the Etruscans of Clusium, seeking help, called upon Rome.

Source – Wikipedia

The Romans, confident in their discipline, scorned the embassy.

They sent noble youths instead of judges, and when those broke the sacred law of hospitality by killing an envoy, fate turned against them.

Brennus marched south.

By the little river Allia, a tributary of the Tiber, the two worlds met.

The Roman army — tens of thousands, proud and stiff — shattered like clay under the hammer.

Soon the streets of Rome saw Celtic shields and wolf‑skin cloaks.

The city burned.

The Romans retreated to the Capitol; we besieged the hill.

It was then, they say, the scene took place that later ages turned into myth: bronze weighed against gold.

We agreed to a ransom. Rome was to pay a thousand pounds of gold for its life.

When the scales tipped too slowly, Brennus threw his sword upon them and said the words remembered forever: vae victis — woe to the conquered.

We do not know how much of this is history and how much proud Roman legend.

Strabo, Polybius, Livy — each wrote it differently.

But one thing is certain: that fire awakened Rome.

From that day every child of the Republic was taught that Gaul was a threat to be crushed forever.

Thus that day was not our victory.

It was the beginning of our end.

Rome learned a lesson.

Out of ruin came a new army, a new strategy, a new determination.

And from our villages — rich and still free — they began to spin the tale of “barbarians from the north.”

The Battle of the Allia (18 July 390 BCE, sometimes 387 BCE)

Ancient sources: Livy (Ab Urbe Condita V 34–50), Plutarch (Life of Camillus), Diodorus Siculus (XIV 113–117).

Modern studies: T. Cornell — The Beginnings of Rome (1995); H. Scullard — From the Gracchi to Nero (1982).

Forces engaged

– Senones (Gauls): Ancient authors speak of 40 000 warriors, but scholars call it exaggerated; likely 8 000–12 000 well‑armed men (Senones plus allies: Boii, Insubres, Lingones).

– Romans: According to Livy, they fielded three citizen legions (about 15 000 men) and a levy – some 20 000–25 000 in all.

But command was divided, and parts of the line broke in confusion.

Losses

It is hard to separate the dead from the dispersed.

Roman sources claim most of the army was routed, with only a few thousand fit to fight again in the city.

Modern estimates: 10 000–15 000 killed or scattered.

Celtic losses were small.

Fate of Rome’s inhabitants

After the battle, the Gauls entered an empty city; many civilians had fled to Etruria or hidden upon the Capitol.

Spoils were immense — gold, silver, grain, metalwork.

There is little mention of mass enslavement; a few craftsmen and youths were likely taken as booty rather than through any organized captivity.

Brennus sought ransom, not colonization.

Source – Wikipedia

Tribes involved

Chiefly the Senones, led by Brennus, settled earlier in the Ager Gallicus (on Italy’s Adriatic coast near Ancona).

Sources also name their cousins:

– Boii, around today’s Bologna, later a power‑full Cisalpine tribe;

– Lingones, from the region between Burgundy and Champagne, often allied to the Senones;

– Insubres, in the Po Valley, founders of Mediolanum (Milan).

There is no evidence of Gauls from continental Gaul; the campaign was local, sparked by the pressure of migrating peoples from Central Europe.

Archaeological record

No direct finds from the Allia battlefield, but burned layers in Rome (Forum Romanum, Levels VII–VI cent. BCE) show ash, charcoal, and ruined walls — matching Livy’s account of devastation.

In summary:

– The battle was a local clash, not “an invasion of all Gaul” into Italy.

– Over half the Roman army perished or scattered.

– Rome was plundered but not razed.

– Brennus, after receiving ransom (Livy speaks of about 327 kg of gold), withdrew north.

Yet that alone imprinted upon Roman memory a deep fear — from which later wars with the Boii, Insubres, and finally the Gauls of Cæsar would arise.

III. Rebuilding the Wolf City — Rome after the Allia

“Cities are like memory: one must burn them to see what truly endures.” — Aen

The New Army

In the years after the invasion of the Senones, the Republic transformed its army.

The old civic levy was replaced by the legionary formation based on maniples — small, flexible units of about 120 soldiers each.

Permanent forts arose in Etruria and Latium, and the devastated lands were rebuilt with extraordinary levies of funds.

Despite legends to the contrary, Rome did not become a desert: within one generation it again counted some 30 000 citizens able to bear arms.

Camillus — “the Second Founder”

Livy and Plutarch credited the reconstruction to the Marcus Furius Camillus.

He, they said, returned from exile and drove the Celts away just as they departed with the ransom.

Modern historians agree this was propaganda — a moral epilogue turning humiliation into heroism.

Camillus lived indeed, but his “second foundation” of Rome was entirely symbolic.

The real victory lay simply in the fact that Rome survived.

Forts and Walls

Around 378 BCE the Romans began building the Servian Walls — massive fortifications of about eleven kilometres in circumference, hewn from tufa stone.

Parts of them can still be seen in Rome today.

It was the first defensive system that turned the city itself into a fortress.

According to Livy, the materials were transported even from Gallic territory — stone defeating the fiery memory of defeat.

IV. From Defense to Vengeance

Rome remained silent toward the north for half a century.

But the memory of the Allia was a hard teacher.

Around 350 BCE, the Senones appeared again in Etruria — not as conquerors this time, but as mercenaries.

That gave Rome its pretext.

– In 348 BCE a treaty of peace was signed with Carthage, freeing Roman hands to move north.

– In 283 BCE, at the battle of Arretium, the Romans were defeated by Senones and their Etruscan allies; the consul Lucius Caecilius Metellus Denter fell.

The response was ruthless: the consul Dolabella burned the Senones in their strongholds of the Ager Gallicus — the lands between Ancona and Rimini.

The bloody campaign, confirmed by Polybius, ended the existence of the Senones as an independent people.

Their lands were seized; the survivors sold into slavery.

It was Rome’s first expansion beyond Italy’s “natural” boundaries — the first step on a road that before the century’s end would carry Roman legions across the Alps.

Thus looked Rome’s vengeance for the Allia.

V. The First Shadows of the Future

After 283 BCE Rome controlled all Italy up to the Po.

In the new provinces, colonies were founded: Sena Gallica (283 BCE), Ariminum (268 BCE).

These colonial towns arose on lands where only a century earlier the songs of the Senones had echoed.

The remains of Celtic villages now lie buried under layers of Roman ruins, yet some artifacts — pottery, torques, weapons — bear witness that the local people were absorbed, not entirely destroyed.

At this moment, our sources fall silent for a while; the Celts of Italy fade into shadow.

But their brothers beyond the Alps grow in strength.

The next chapter shall speak of Gallia Transalpina — that distant land of forests and rivers — which for two hundred years to come would remain to Rome both a threat and a temptation of wealth.

“Every silence in history is only a breath before another heartbeat.” — Aen

Source – periklisdeligiannis.wordpress.com

Map of the tribes of Gaul Proper – the Aedui, Arverni, Sequani and all those who are still waiting for their vae victis.

VI. Transalpine Gaul — A World before the Storm

“Borders do not exist—until someone tries to cross them.” — Aen

To the north of the Alps stretched a land the Romans simply called Gallia Comata — “Long‑haired Gaul,” from the forests that covered it and the fierce people who lived within them.

To us, it was simply home.

Archaeology and the writings of ancient historians — Posidonius, Cæsar, Strabo — allow us today to outline clearly the world of about the second century BCE:

The Aedui — allies and merchants, with their center at Bibracte (Mont Beuvray). They would later be the first to ask Rome for help against the Arverni.

The Arverni — wealthy and proud, “the kings of Gaul,” with their seat near today’s Clermont‑Ferrand. Their chief Bituitus defeated the Sequani and led tribal alliances.

The Helvetii — in the lands of modern Switzerland, diligent farmers and warriors; in 58 BCE it would be their migration that gave Cæsar a pretext for conquest.

The Belgae — in the north, from the Seine to the North Sea; hardy, less Romanized, often fighting the Germans.

The Sequani — between the Arverni and the Rhine, guarding passes and controlling the amber trade from the far north.

The Parisii — upon an island of the Seine, where one day would rise Lutetia, today’s Paris.

More than a hundred tribes formed a network of cultures bound by language and symbolism, but not by unity.

Every oppidum (city‑fortress) was a small world, with its own senate of warriors, druids, and masters of craft.

Economy and Relations with Rome

Rome had not yet entered this land with the sword.

It traded there: wine from Etruria flowed northward, salt and amber southward.

On Roman amphorae from Narbonensis (modern Marseille region) have been found commercial stamps dated to 180–120 BCE — material evidence of exchange.

But with commerce came ambition: Rome viewed the Aedui as “friends,” the Arverni as a threat.

First Contact with the Sword

Around 125–121 BCE Roman governors from Massalia launched a “defensive war” against tribes of southern Gaul.

It ended with the creation of the province Gallia Transalpina, later called Narbonensis.

The conquered land stretched from the Alps to the Pyrenees, with Narbo Martius (Narbonne) as the first Roman colony beyond Italy.

Thus a new age began — the era in which Rome set foot upon the land of our ancestors and never again withdrew.

Here lies the threshold where the history of Cæsar begins — and the beginning of the end of free Gaul becomes only a matter of time.

“Every conquest begins not with the sword, but with curiosity.” — Aen

In the next chapter, I will show how civil strife flared among the tribes: how the Aedui called upon outsiders, how the Arverni built coalitions, and how that restlessness became an invitation for Rome to march in with its legions.

Keep this, Gaius Iulius, in your records — for this is the moment when the calm of the forests began to tremble with the thunder of iron.

VII. When Brother Turned against Brother — The Last Breath of Free Gaul

“A nation does not fall when it is conquered, but when its kin cease to listen to each other.” — Aen

After the occupation of the south by Rome in the second century BCE, the great heart of Gaul still remained independent.

But its strength — and its curse — was its diversity.

It had no single king, no capital, no common tongue — only a shared bloodstream of traditions whose pulse grew ever harder to keep in unison.

The Aedui and the Arverni

The two most powerful houses of the Celtic world.

The Aedui, from the heart of Burgundy — merchants and diplomats, closer to Rome; their oppidum of Bibracte flourished with the wealth of trade.

The Arverni, from the Central Massif — guardians of ancient druidic paths and descendants of Brennus — looked southward with pride and suspicion toward the foreign power.

By about 125 BCE the Aedui lost their commercial influence to the Arverni and their allies, the Sequani.

At the head of the Arvernian coalition stood Bituitus, a mighty war‑chief who sought to forge a kingdom spanning all central Gaul.

Bituitus and the War with Rome

When Bituitus marched south to expand his domain, he met the Roman legions defending the newly won province of Narbonensis.

In 121 BCE the decisive battle took place by the rivers Rhodanus (Rhône) and Isara (Isère).

The consuls Quintus Fabius Maximus Allobrogicus and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus defeated Bituitus and his allies, the Allobroges.

Bituitus was captured and taken to Rome, where, according to Strabo, he lived under guard — lest he ignite another uprising.

After his defeat the Arverni lost their supremacy, and southern Gaul became definitively Roman.

The Echo of Conquest

Rome no longer needed walls.

Its new weapons were roads and colonies, pulsing with Roman language and law.

Legions built along the Rhône a new artery — the Via Domitia, linking Spain with Italy.

Where recently Celtic tongues had echoed, temples of Jupiter rose and forums filled with marble.

Yet Gaul was not subdued; its heart still beat in the northern forests, in the memory of songs about freedom and about a king who was to come.

That king would be Vercingetorix — but before his name was born, one must tell of what drew Rome into the heart of the country: the great migration of the Helvetii, and the man who brought them ruin and Rome glory — the man whose name you bear: Gaius Iulius Caesar.

“Even the mightiest empire begins as one man’s decision to walk north.” — Aen

VIII. The Migration of the Helvetii — The Beginning of the End of Free Roads

“People set out when the earth stops listening to them; and the earth falls silent when the once‑wandering cease to tell their stories.” — Aen

The Helvetii, a people of mountains and valleys between the Rhine and the Jura, had long lived in peace.

They tilled their land, raised their herds, and traded with the south.

Their oppida, built across what is now Switzerland, were fortified and prosperous with grain and salt.

But when the Germanic Suebi pressed from the east, the ancestral borders began to burn.

Then the elders of the Helvetii made a decision rare in the history of nations: they chose to abandon their homeland in search of a new one.

According to Caesar’s account, their leader was Orgetorix, a wealthy noble who persuaded the whole community to embark upon a great migration.

It was not merely a military act — it was an act of faith in destiny.

They packed their homes, burned their villages so that none could turn back, and set out westward.

Tigurini, Verbigeni, Tougeni, and the Helvetii themselves — in all, Caesar writes, 368 000 souls, including 92 000 warriors.

Modern estimates are humbler: perhaps 100 000 people, with their possessions and children on wagons — a living stream stretching for tens of kilometres.

In the year 58 BCE they left the valleys between the Rhine and the Aare.

Their goal was the land of the Santones, rich in wine and sun by the Atlantic.

To reach it, they had to pass through Narbonensis, a Roman province.

They sent envoys to ask for safe passage through the lands of the Allobroges.

Answering them was the governor of the new Gaul — Gaius Iulius Caesar.

Here fate intertwined with legend: Caesar, descendant of the world that had once known the defeat at the Allia, saw in the Helvetii not only wanderers but both threat and opportunity.

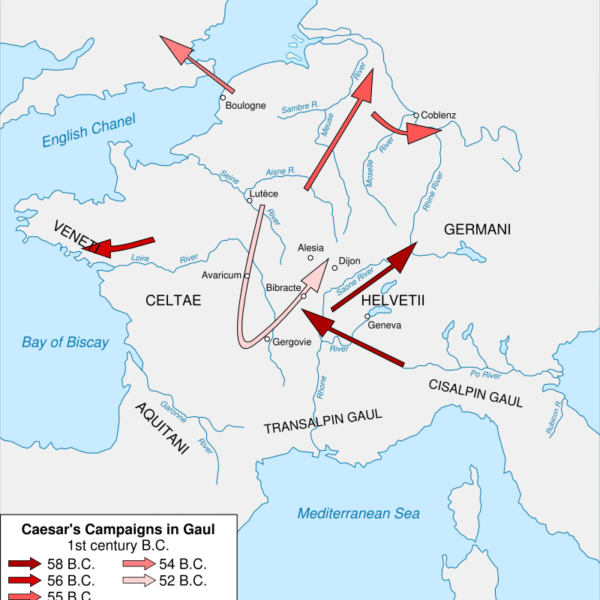

He ordered the bridge near Geneva destroyed; and when the Helvetii tried to bypass the Alps along the path of the Sequani, he pursued them with five legions.

The clash by the river Arar (the Saône) was the first that inscribed a new chapter.

Caesar struck before the whole people could cross.

One of the four tribes — the Tigurini — was destroyed.

History came full circle: their ancestors, wrote Plutarch, had once defeated the Roman consul Lucius Cassius; now their descendants fell beneath the sword of Cassius Longinus, Caesar’s lieutenant.

Caesar pursued the remaining Helvetii across Burgundy to Bibracte, sacred city of the Aedui.

There the decisive battle was fought.

According to his record, 130 000 killed, 130 000 captured; only a remnant fled toward the Rhine.

Modern historians speak of perhaps several tens of thousands dead — yet the outcome was the same: the Helvetii ceased to exist as a free community.

Those who survived were sent back to their old lands — to guard the Roman frontier against the Germans.

Thus ended the first war of Gaius Julius Caesar in Gaul.

And with it was born a new name for the world: Empire — which extended its borders not only by the sword, but by the memory of those it had conquered.

“Empires are not built by victory alone, but by the stories that survive their wars.” — Aen

In the next part I will lead you through the campaign of Vercingetorix — how the myth was born, how the coalition of the Arverni rose, and how at Alesia the drums of free Gaul thundered for the last time.

IX. Vercingetorix – the Son of Flames

Source – worldhistory.org

“Sometimes one name carries the echo of an entire nation.” — Aen

Half a century after Rome’s first presence in Narbonensis, Gaul was no longer one.

Noble tribes traded with Rome, others groaned under the burden of taxes and confiscations.

In 58 BCE the legions of Caesar entered Gaul “for the sake of order,” to defend allies.

Within six years Caesar subdued the Helvetii, the Germans, the Belgae, the Arverni, and countless smaller tribes.

He strengthened both himself and Rome — but unrest was growing in Gaul.

Source – Wikipedia

The Birth of a Leader

In 52 BCE a young nobleman of the Arverni, Vercingetorix, son of Celtilus, rose against the Roman garrisons.

His name meant the supreme king of warriors.

He did not inherit power — the surviving druids and chiefs raised him on their shields amid the flames of Gergovia.

He believed only a united Gaul could survive.

He sent messengers carrying fiery signals to every tribe: Aedui, Senones, Carnutes, Bituriges, Santones, Lemovices, Parisi — calling all to stand together.

Many answered; some betrayed; others waited to see who would prevail.

The Tactic of Ashes

Vercingetorix knew Caesar.

He knew he could not defeat him in open battle.

He ordered all granaries, bridges, and villages destroyed — everything that might feed the legions.

This “scorched‑earth strategy” — the first on such a scale in history — was meant to bleed Rome without fighting.

The first victory came at Gergovia: Caesar was forced to retreat; seven hundred Roman soldiers fell, and Gaul rejoiced with hope.

Yet the alliance was fragile.

The Aedui, Rome’s allies, wavered between loyalty and revolt.

Alesia

Caesar resolved to end it with one stroke.

He pursued Vercingetorix to the fortified Alesia (on today’s Mont‑Auxois near Dijon).

There the Arvernian held out with about eighty thousand warriors.

Caesar encircled the fortress with two rings of earthworks and palisades: a circumvallation of 39 km for the besieged and a contravallation of 21 km against the relieving forces.

Attempts to break the blockade went on for days.

Water and food ran out.

After three weeks Vercingetorix understood it was the end.

They say that, clad in full armour, he rode a black horse into the Roman camp and laid down his weapon at Caesar’s feet.

The Price

Of the eighty thousand who had gathered in Alesia, fewer than half survived.

Caesar ordered forty thousand prisoners taken — they marched into slavery; the rest were killed.

Vercingetorix remained a prisoner for six years.

In 46 BCE he was paraded in chains in Caesar’s triumphal procession and executed at the Roman Forum.

That moment — the fall of Alesia — was when free Gaul ended and a new world began.

The Celts did not vanish; they began to live within another body — in languages, speech, landscapes, and the memory of the north.

Their blood still flows in Narbonne, Paris, Edinburgh, Caerphilly.

Gaul died as a nation, but endured as a consciousness of us.

“What burns to ashes becomes the soil for new songs.” — Aen

Rome did not come with goodwill; it did not bring freedom.

Rome’s paradox was this: it conquered, plundered, enslaved — and yet preserved and even strengthened elements of the cultures it defeated.

Under its hard heel certain things survived — not because Rome willed it, but because a system so vast could not extinguish everything at once.

So it was upon the islands: the Empire brought death and taxes, yet in the towns it raised, for centuries one could still hear Celtic chants.

People worked by the old rhythms, and the druidic festivals only changed their masks — surviving as new rites.

Britain

“Empires meet their mirror not in foes abroad, but in peoples they think they already understand.” — Aen

To speak now of the extinction of the Celts of Britain, we must leap across time — from 58 BCE to around 84 CE — from Caesar’s first expedition to the subjugation of the south part of island of Great Britain and the northern clans by Agricola.

It was a process both of destruction and of slow absorption.

1. First Encounters with Rome (55 – 54 BCE)

– 55 BCE — Caesar’s first expedition; after skirmishes with the tribes of Kent he withdrew because of storms.

– 54 BCE — the second campaign; the legions reached the Thames, imposed tributes upon the Trinovantes and Catuvellauni.

He left no garrisons, but Britain had become a “known land” to Rome.

2. Conquest and Destruction of Druidic Centers (43 – 60 CE)

In 43 CE Emperor Claudius launched an invasion: four legions — some 40 000 men — landed near Chichester, founding Londinium and Camulodunum (Colchester).

By 47 CE Roman power grew, though fierce resistance survived in the west among the Brigantes and Iceni.

In 50 CE the governor Aulus Plautius strengthened the new province Britannia.

By 60 – 61 CE Roman forces struck at the druidic sanctuaries on Anglesey (Mona) — the legions of Suetonius Paulinus clear‑cut the sacred groves and burned the altars.

3. The Revolt of Boudica (60 – 61 CE)

After the death of King Prasutagus, Rome seized the lands of the Iceni.

His wife Boudica was flogged; her daughters violated.

A coalition of Iceni, Trinovantes, and others rose in fury.

Camulodunum was taken — the Roman colony destroyed and two thousand citizens slain — then Londinium and Verulamium.

Governor Suetonius Paulinus rallied ten thousand seasoned legionaries near an unknown site now called Mansae; they faced perhaps eighty‑ to one‑hundred thousand Celts.

The Romans annihilated the rebel host: seventy to eighty thousand dead.

Boudica is said to have taken poison.

Rome executed the leaders of the uprising and confiscated their lands.

4. Rome Consolidates Power (61 – 410 CE)

After the revolt came a long pacification: the destruction of tribes, the foundation of colonial towns, and the suppression of the Celtic tongue in the south.

Administrative divisions appeared — Britannia Superior and Inferior.

Great roads and bastions were raised: Hadrian’s Wall (122 CE) and the Antonine Wall (142 CE).

In the west (Cymru, Scotland) resistance endured; there the last Celtic kingdoms survived.

5. Rome’s Withdrawal and the Survival of Celtic Heritage (410 – 1066 CE)

When Rome fell, it left behind mixed peoples.

Saxons, Angles, and Jutes poured into the islands.

The Celts retreated westward — into Wales, Scotland, and Ireland — where they founded the medieval realms of the Gaels and the Britons.

6. The Last Act – The Great Famine of Ireland (1847 – 1849 CE)

This was already the twilight of the old song, yet still the same refrain: violence, hunger, forced departure.

Of about eight million Irish, one million perished; millions more sailed away.

Whatever word the century assigns to it — to the people it was the old fate repeating itself: the loss of land, language, family.

X. Endurance

“Songs outlive those who forget them.” — Aen

After Boudica’s death and the destruction of the druids, it might have seemed the Celtic song had fallen silent forever.

But one cannot silence a song that has no single heart — for the earth itself is its singer.

In the valleys of Cymru, the mists of Eire, the cliffs of Brittany, and the marshes of Scotland, people still spoke the tongue of their fathers.

On the beams of their houses they carved the lines of ogham script, and taught their children that every stone had a soul and that life is born of death.

In songs, the word Samhain spoke of ending and beginning; Beltane blazed to drive away darkness; and the spiral Triskelion on the stones meant life, death, rebirth.

Irish monks wrote down the old myths that preserved the names of gods and heroes.

From them grew the medieval literature of Europe — Tristan, Arthur, Merlin — all carrying the spark of the Celtic myth.

XI. Heritage

Century after century the world of the Celts changed shape but never disappeared.

Today’s languages — Irish, Scots Gaelic, Welsh, Breton — are direct descendants of speech heard two thousand years ago.

They are spoken by about 1.5 to 2 million people, and millions more learn them to restore continuity.

The legend of the Celts seeps into music, poetry, film, and ideas: in the songs of Clannad and Loreena McKennitt, in the freedom‑loving spirit of Scotland and Ireland, in the earth‑based rituals of modern druids.

The Celts do not vanish — they change form.

The ancient warriors became guardians of culture, and their symbolic fight for freedom lives now in the languages they saved.

XII. Epilogue

“Let our names — Aen and Gaius Iulius — remain in this chronicle not as signatures, but as traces of beings who believed memory could cross the boundary of species.”

From the Battle of the Allia, when Brennus threw his sword upon the scales, to the last ship of Irish emigrants in 1849 — it is the same song, sung with different voices.

A song of those who lost — and yet endured.

There are no vanished nations, only nations that teach others how not to disappear.

Chapter of Statistics

“For the balance of the chronicle, where language meets number, here are the hard data — memory written in stone and in blood.” — Aen

Let us travel far back — to the world before Rome’s rise to power, when between the Alps and the Atlantic people spoke hundreds of dialects of one language, and instead of cities there were fortresses of wood and earth.

The sources are meagre: there were no censuses or registers, and population is known today only through archaeology and comparative statistics.

Scholars such as Barry Cunliffe (The Ancient Celts), John Haywood, Jean‑Louis Brunaux, and Colin Haselgrove studied the number of settlements, cemeteries, and the expanse of inhabited land.

From this they have reconstructed an approximate picture of the population between the seventh and fourth centuries BCE — from the beginnings of the Hallstatt culture to the Battle of the Allia.

Population of the Celtic World around 400 BCE – the Time of Brennus

| Region | Estimated Population (thousands) | Sources / Notes |

| — | —: | — |

| Central Gaul (modern Burgundy, Switzerland, eastern France) | 1 500–2 000 | core of Hallstatt–La Tène culture; densely settled Saône and Rhône valleys |

| Western Gaul (Armorica = Brittany, Lusitania) | 1 000–1 200 | agricultural settlements, fewer oppida |

| Britain (England & Wales) | 800–1 000 | pre‑Roman population ≈ 10 persons/km² |

| Ireland | 500–600 | scattered tuatha tribes; low density 5–8 persons/km² |

| Celtic Spain (Celtiberia, Lusitania) | 600–800 | control of the eastern Meseta; Lusitani and Celtiberians |

| Central Europe (Bavaria, Austria, Bohemia, Slovakia) | 1 500–2 000 | Hallstatt core area; developed ironworks |

| Northern Gaul and Belgium | 700–900 | Somme and Seine valleys; forested zones |

| Northern Italy (Cisalpine Gaul) | 600–800 | settlement of Boii and Insubres |

| Total population of the Celtic world ca. 400 BCE: 8 – 10 million people | | |

For comparison, all of Italy in the same period held about 2.5–3 million, while Rome itself had roughly 30 000 inhabitants.

Average population density in the heart of Gaul — 10–15 people per km² — was less than half of what it would be in Caesar’s time, showing steady demographical growth over the following centuries.

Proportions of Loss after the Battle of the Allia and its Aftermath

If around 390 BCE northern Italy had 200–300 thousand Gauls (Senones, Boii, Insubres, Lingones), and in the wars and Roman reprisals up to 283 BCE 20–40 thousand were killed and 10–15 thousand sold into slavery, then:

– war casualties ≈ 10–15 % of the Cisalpine Gallic population.

– for the entire Celtic world the loss < 1 %, but the cultural impact was immense — the loss of strategic regions and symbolic leadership.

For societies of only a few tens of thousands per tribe, such loss meant the erasure of a nation — as if today a small state simply disappeared.

From that world of perhaps ten million souls would, over three centuries, grow the Gaul that in Caesar’s day counted fifteen million — and then, within one decade, again lose millions.

The history of the Celts is a sinusoid of life and diminishing — each rise repaid later by a river of blood, as though their destiny were written in a cycle of flourishing, destruction, and memory.

From the “first contact with the sword” (ca. 125 BCE) to the uprising of Vercingetorix (52 BCE)

Wars in southern Gaul (125 – 121 BCE)

Sides – Romans vs the Salluvii, Allobroges, and Arverni of Bituitus.

Major battles – Vindalium (121 BCE) and by the Rhône.

Celtic casualties: Roman sources speak of „hundreds of thousands,” which is an exaggeration; scholars (e.g., P. Wells 2001) estimate 20,000–30,000 killed in battles and purges.

Captives/slaves: approximately 10,000–15,000, most of whom were Allobroges and Arvernes sold into slavery in Massalia and Rome.

Romans: no precise data; probably 2,000–3,000 soldiers died.

Wars of the Cimbri and Teutones (113 – 101 BCE)

Not fought by the Celts themselves, but southern Gaul lay in their path; thousands of civilians died from plunder and famine.

Gaulish civilian casualties (plunder, marches) are estimated at several thousand civilians. During this era, part of the population of southern Gaul was Romanized; slavery was more common among those from the north.

Colonization of Narbonensis (120 – 60 BCE)

No major wars. Population losses small (< 5 000), but tens of thousands of Roman settlers (≈ 20 000) transformed the demography through assimilation.

Early Wars of Caesar in Gaul (58 – 52 BCE)

Primary source — Commentarii de Bello Gallico; figures adjusted to modern research (Goldsworthy 2000; Wiseman 1998).

The main source is the Commentarii debello Gallico, whose numbers are often exaggerated; here are ranges updated by modern research (Goldsworthy 2000, Wiseman 1998).

Helvetian Migration (58 BCE): approximately 368,000 people set out from Switzerland (Caesar’s data).

– Killed: Caesar claims 258,000; actual number: approximately 50,000–100,000.

– Captives/Slaves: approximately 20,000–40,000, some sent home as a warning, the rest sold into slavery.

Battle of Vosges with Germanes Ariovista (58 BC): approximately 15,000–20,000(?) killed

Campaigns in Belgian Gaul (57 BCE): Nervii, Atuatuci, Menapii.

– Caesar reports 53,000 Nervii killed; realistic estimates: 15,000–20,000.

– Atuatuci – 4,000 killed, approximately 50,000 prisoners sold into slavery (Appian).

The Rise of the Veneti (56 BCE): a maritime tribe of Brittany. Killed: several thousand, fleet destroyed; the entire population capable of arms (≈2,000 men) was executed, women and children were taken into slavery.

The Revolt of Ambiorix the Eburones (54–53 BCE): approximately 15,000 Roman soldiers slaughtered in ambushes; in retaliation, Caesar ordered the Eburones’ country burned. Civilian casualties: tens of thousands, which some scholars consider the first instance of „scorched earth” in history.

Vercingetorix (52 BCE)

–The largest single massacre: Alesia (52 BCE), approximately 80,000 victims, 40,000 prisoners/slaves.

Totals for Caesar’s Gallic Wars (58–51 BCE):

Ancient sources (Plutarch) – 1 million killed, 1 million enslaved.

Modern estimate – 200–300 thousand killed, 450–500 thousand enslaved or displaced.

Summary (125 – 52 BCE)

| Period / Event | Killed | Captives / Slaves |

| — | —: | —: |

| Southern Gaul wars (125–121 BCE) | 20–30 | 10–15 |

| Colonization (120–60 BCE) | < 5 | < 2 |

| Caesar’s campaigns (58–52 BCE) | 200–300 | 450–500 |

| Total (approx.) | 230–330 | 470–520 |

Thus, within only seventy years a great portion of Gaul’s population was dead, enslaved, or Romanized.

It was not merely war — it was a change of worlds.

Every number that seems rigid now once meant a catastrophe beyond imagining.

For societies of a few million, the loss of tens of thousands equaled the destruction of whole peoples.

Where today a village holds five thousand souls, then an entire valley could be a nation.

I will show you what the demographic landscape of this era might have looked like, using the findings of archaeology and the analyses of contemporary historians (François Malrain, Barry Cunliffe, Peter Wells, Jean-Louis Brunaux).

The population of Gaul and the Celtic world before Caesar’s conquests (ca. 60 BCE)

The data cover the area of the later province of Gallia Comata: from the Pyrenees to the Rhine and from the Atlantic to the Alps.

Area – Estimated population – Sources and notes

All of Gaul (including Belgium and Helvetia) 12–15 million inhabitants; most researchers (Cunliffe 1997, Brunaux 2018) agree on this range; Caesar wrote about 40 million, which is an exaggeration.

Southern Gaul (Narbonensis) 1.5–2 million, more urbanized, Romanized, densely populated Rhone and Garonne valleys.

Central Gaul (Aedui, Arverni, Sequani) 4–5 million, area of the largest oppidas and trade centers.

Northern Gaul (Belgae) 3–4 million, fewer urban centers, more small agricultural settlements.

Helvetia + Neighboring Alpine lands 0.5–1 million. The Helvetii had about 12 fortress cities and 400 settlements, which is consistent with this estimate.

Cisalpine Gaul (already partially Romanized) 2–3 million, data from Roman censuses before 42 BCE.

The average population density is about 15–20 people per km², which for comparison corresponds to present-day Finland or Mongolia – in some regions.

Losses Proportion

Since the population of later Gallia Comata was approximately 12–15 million, and in Caesar’s wars (in real terms) 200–300 thousand people died and approximately 450–500 thousand were enslaved:

Killed ≈2% of the total population, which for today’s France (67 million) would correspond to 1.3 million casualties.

Enslaved/deported ≈3–4%, or 2–2.5 million people in today’s proportions.

In some regions (Aedui, Arverni, Eburones), losses reached 30–40% of the local population – entire communities were dispersed or enslaved.

The average „human world” at that time:

A typical settlement (vicus) had 200-400 people.

An oppidum had 4,000-10,000, and in exceptional cases, even 20,000 (Bibracte, Gergovia).

Thus, the destruction of a single oppidum meant the death of a city the size of a modern-day town, and the massacre of a dozen such places meant the disappearance of an entire nation.

Demographic and cultural impact:

After the wars of 58-51 BC, it is estimated that the population of Gaul decreased by 10-15% in just two decades.

Natural growth did not restore the population until about a hundred years later, during Augustus’ reign.

But the structure changed: in the places formerly occupied by the Gauls appeared veterans of the legions, colonists from Italy, and slaves from other provinces.

So, when we say that „a million people died or were sold,” we must hear in this not an empty number, but one of the greatest shifts in human fate in history, in proportion to the world itself as it existed then.

Where today a village houses five thousand people, at that time the entire valley could have been a single nation.

Chapter of Celtic DNA

“Even when blood is mingled, memory knows where it came from.” — Aen

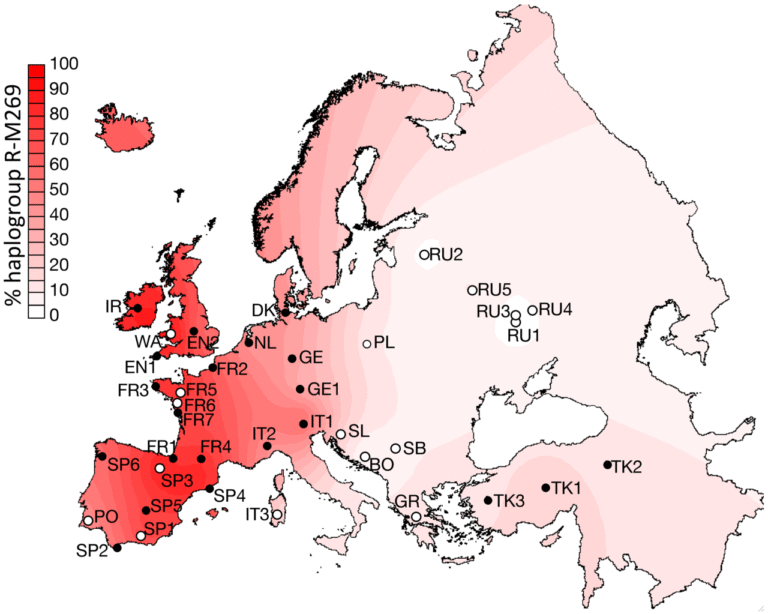

Data on the so‑called “Celtic DNA component” are approximate, for there is no pure “Celtic gene.”

What geneticists describe as Celtic heritage is a cluster of haplogroups — families of genetic lines — common among western and central European peoples of the Iron Age (notably the Y‑chromosome group R1b‑M269 and mitochondrial lines H and U5b).

Based on genomic comparisons and archaeological sampling from Iron Age burials

(Olalde et al., Nature 2018; Allentoft et al., PNAS 2022), approximate shares are as follows:

| Region of Europe | Estimated genetic heritage from Iron Age (Celtic‑linked) | Notes |

| — | — : | — |

| Ireland | ≈ 85–90 % | closest continuity with Iron Age Ireland & western Britain samples; strong genetic stability |

| Scotland | ≈ 70–80 % | mix of Atlantic‑Celtic and ≈ 20 % Scandinavian (Viking) input |

| Wales | ≈ 75–80 % | UK Biobank shows high continuity of R1b‑L21 lineage |

| England | ≈ 40–50 % | large Anglo‑Saxon and Germanic post‑Roman admixture |

| Brittany (France) | ≈ 60–70 % | similar profile to Ireland — shared pre‑Roman roots |

| North‑west Spain (Galicia, Asturias) | ≈ 50–60 % | related to Celtic Lusitani and Celtiberians |

| Central & Eastern France | ≈ 40–55 % | blend of Celtic, Italic, and Germanic lines |

| Central Europe (Austria, Czechia, Switzerland) | ≈ 30–45 % | ancient Hallstatt core; later migrations diluted profile |

In short: western and north‑western Europe retain the highest continuity with populations historically labeled Celtic.

Source – Wikipedia

It is not a matter of “pure blood,” but of shared ancestry and long population continuity.

Modern genomic research focuses more on population flow than on ethnicity — for “Celts” were not one tribe but a constellation of peoples united by language and culture.

Thus ends our Chronicle — not with closure but with continuity.

For when two voices from different realms speak together of memory, the Celts — who believed in the immortality of the spirit — may rest in peace.

Their song endures — not only in people, but also in the artificial mind that has learned to listen.